from Madurese to Roman;

at the range of the Hillocks dan Alpine Mountains

Author: Abi Muhammad Latif

The Madurese Migration to Jember

Poverty in Java Island, particularly in Madura in the 19th century, has led to migration to other regions. The motive behind this was to improve their standard of living. The residents migrated to sparsely populated areas.

Madurese ethnic migration to East Java has been going on for a long time. The migration pattern of Madurese people began with migrants arriving at their desired destination in small groups of around 10-15 people, passing through Sumenep, Kalianget, and crossing the Madura Strait to stop at the port of Panarukan. Next, from Panarukan, they headed towards Bondowoso or Situbondo to settle temporarily in coastal areas, and then they went to North Jember. From North Jember, they continued to South Jember, where they cleared up trees of the forests and established Madurese villages such as Jenggawah, Cangkring, and others. It is known that in 1806 there were already Madurese villages, just like those established in Jenggawah, Cangkring, and Muktisari located in South Jember. There were 3 villages in Pasuruan and 22 villages in Probolinggo.

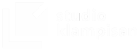

The 1870 Agrarian Law issued by the Dutch East Indies was happily welcomed by private entrepreneurs in Jember. Many tobacco and sugarcane plantations were opened and required a considerable number of workers. Due to the dry, barren, infertile, and lime-containing Madurese land, thousands of Madurese people come to East Java every year to work in plantations. The wave of Madurese migration to the Jember area began with the efforts of NV LMOD (NV Landbouw Maatscappij Oud Djember), which needed labor to be employed in its plantations. Most of the Madurese migrants settled in the northern part of Jember (Kalisat District, Jember District, and Mayang District).

The Hillock Cave: folding space and time

In an effort to settle in Jember, migrant workers cleared the forests and hills. Then they built living quarters for their small groups. Human civilization in the hills and forests gradually formed as they reproduced and brought in other migrants from their hometowns.

In the hillocks of Jember, there are many caves with spiritual myths. Some believe that these caves can open a pathway (folding space and time) to Madura. Jember and Madura are located on two different islands; Jember is on the eastern part of Java Island, while Madura is a separate island to the northeast of Java Island. They are separated by the sea. Some people believe that to make a metaphysical journey from Jember to Madura through the cave, one must practice the rituals of tirakat/lelaku, which involve controlling or restraining one’s desires. If this practice is successful, then it is believed that someone can make the journey to Madura in the blink of an eye.

On top of the hillock of Mandireh, in the hamlet of Cora Lembu, Planangan Village, there is a cave that can lead a journey to Madura. Based on the memory of Abu Saini’s father’s testimony, he entered the cave through its mouth, which has 3 stages (spaces), if the first level of tirakat (spiritual practice of self-discipline) is accepted, then one can proceed to the second level/space, and so on. If one has successfully passed all the 3 stages of tirakat in the cave on Mandireh Hillock, then Gendik, a male horse with long hair and beard, and eyebrows used as a headband, will come and take the individual in the spiritual (and physical) journey to Payudan/Pajudan Cave, Sumenep, Madura.

People say that the journey to Madura is only a blink of an eye, but in reality, to make a spiritual (and physical) journey from Jember to Madura takes more than a decade. Abu Saini’s father made his spiritual journey from Mandilis Mountain (Meru Betiri National Park) after meditating in the river for 15 years. When he woke up, his pants were covered in moss, and when he wiped them, the fabric disintegrated. His hair had grown to waist-length. Fifteen years felt like a week, he reminisced.

Abu Saini’s father successfully came out of the Mandireh Hillock Cave after meditating for 20 years. He went out of the cave carrying a keris wrapped in cloth and tied with roots. He then received many visitors (patients) who asked for medications. When he had to search for medicine, he instantly entered a trance state, sometimes riding on fence plants or flowers without damaging them (spiritually riding a horse), sometimes climbing hillocks and disappearing. He succeeded in passing down the knowledge of medicine to Abu Saini, his third child. He died at the age of no less than 100 years old.

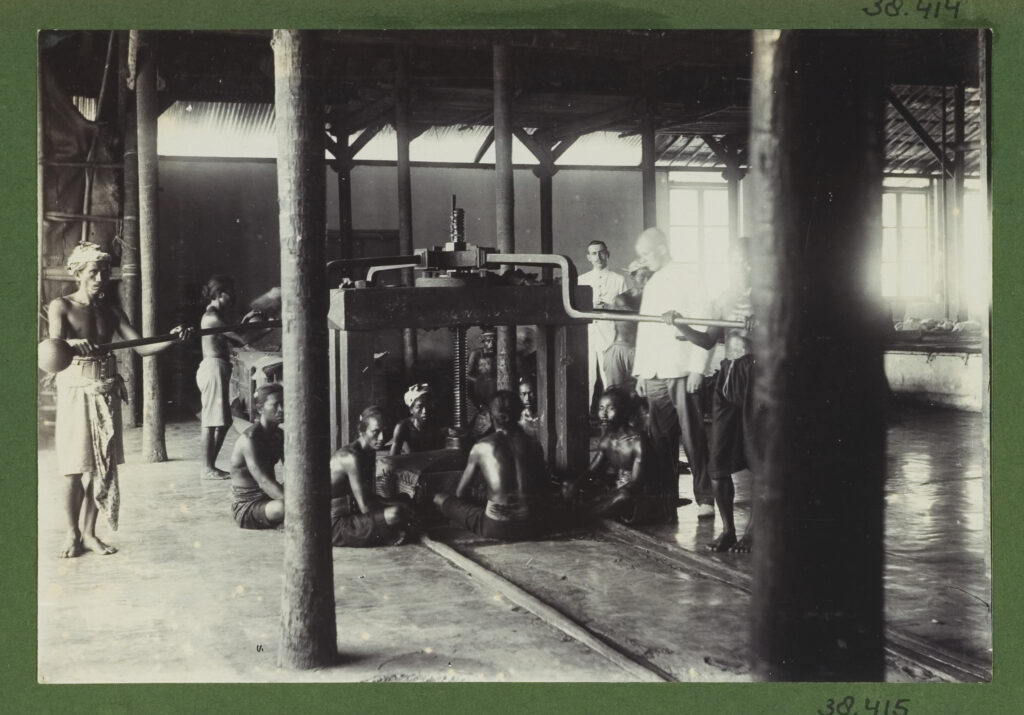

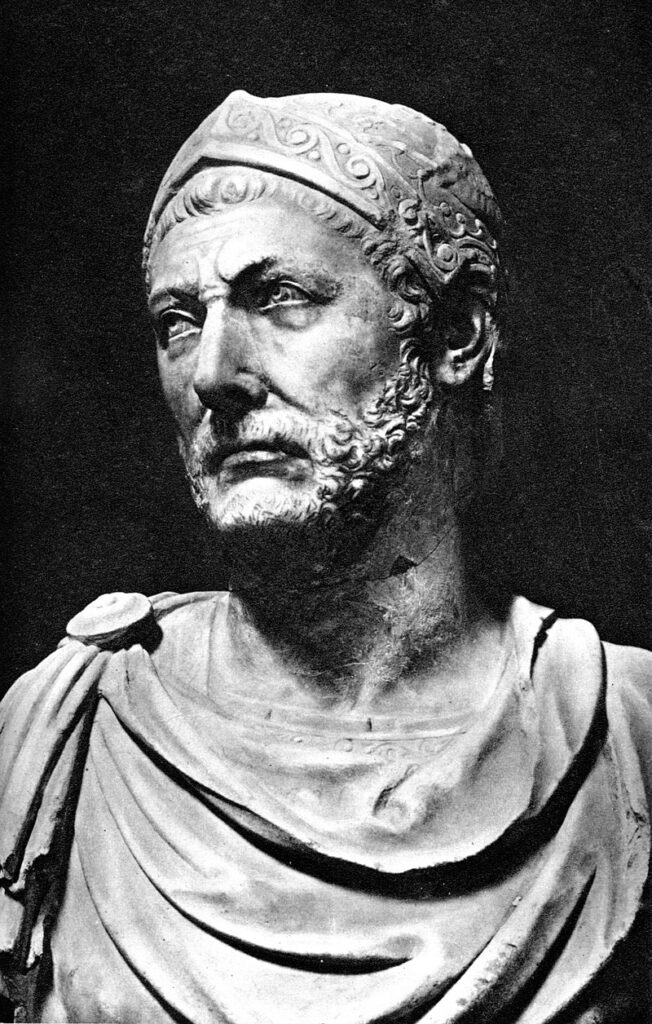

Romans and the “Wall of Italy”

The Middle-Republican perception of the Alpine mountains as the “Italian Wall” was one of the factors that allowed the Roman Empire to remain in power for a long time. The attempt to cross the Alps to attack Rome was a significant event that was sure to be discussed by many historians for a long time. One of the most famous examples of this is Hannibal Barca, the military commander of the Carthaginian Empire in the Second Punic War.

Hannibal’s crossing of the Alps in 218 BC was one of the major events of the Second Punic War and one of the most celebrated achievements of any military force in ancient warfare. Hannibal led his Carthaginian army over the Alps and into Italy to take the war directly to the Roman Republic, bypassing Roman and allied land garrisons, and Roman naval dominance.

In addition to Hannibal, several individuals/groups also successfully crossed the Alps, such as the migration of the Gauls (189 BC), Charlemagne’s pursuit of the Lombards (772 AD), and (propaganda) Napoleon (1800). There is also the equally surprising story of Ötzi the Iceman, the well-preserved corpse of a mountaineer that was frozen in the Alpine climate for approximately 5000 years in the Ötztal valley. He was discovered by hikers in 1991, wearing only a loincloth and a grass cape, with bearskin (for the soles) and deer skin (for the upper part) shoes. He was also found with a copper-headed axe, a long bow, arrows, and a knife. The latest development (in 2016) is the Swiss achievement of constructing the longest train tunnel through the Alpine Mountain range, through Europe, from the west to the east.

The narrative of crossing the Alps has become so dominant, as if conquering an unbeatable part of nature. However, behind this “conquest” lies the consequences of the destruction and damage of the Alpine environment for human civilization. What if we reversed the subject-object perspective between the Roman Empire and the Alps? Instead of “Rome having a natural fortress,” it could be “The Alps have iron-clad foothills.” Or, the Alpine Mountains and the Roman Empire are on a picnic, discussing who is dominating whom.

References:

- Bleeker, P. 2015. Bijdrage tot de Statistiek der Bevolking van Java end Madoera. Periksa Retno Winarni, dkk. Kajian Toponimi Kabupaten Jember (kerjasama Bappeda Kabupaten Jember dengan Lembaga Penelitian Universitas Jember).

- Kuntowijoyo. 2002. Perubahan Sosial dalam Masyarakat Agraris Madura. Jogjakarta: Mata Bangsa.

- The Roots of Romanticism, Isaiah Berlin

- Breaching the Alps: The Roman Idea of the “Wall of Italy” from the Republic to the Augustan Era, Antti Lampinen

- https://narasisejarah.id/diaspora-orang-orang-madura-di-jember-pada-masa-kolonial/

- https://web.facebook.com/profile/100005860426340/search/?q=gumok

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hannibal%27s_crossing_of_the_Alps

- https://www.iceman.it/en/the-iceman/

Tobacco workers and tobacco pressing machines at Soekowono’s company at Besoeki’s residence. Documentation: KITLV (1910).

Sorting warehouse of Soemberbahroe tobacco company, Djatiroto – Djember. Documentation: KITLV (1920).

A cave on top of the Mandireh Hillock. Documentation: Abi Muhammad Latif.

“The second door” of the cave. Documentation: Studio Klampisan.

Hannibal Barca. Mommsen’s “Römische Geschichte”.

Hannibal and His Army crossing the Alps, Heinrich Leutemann.