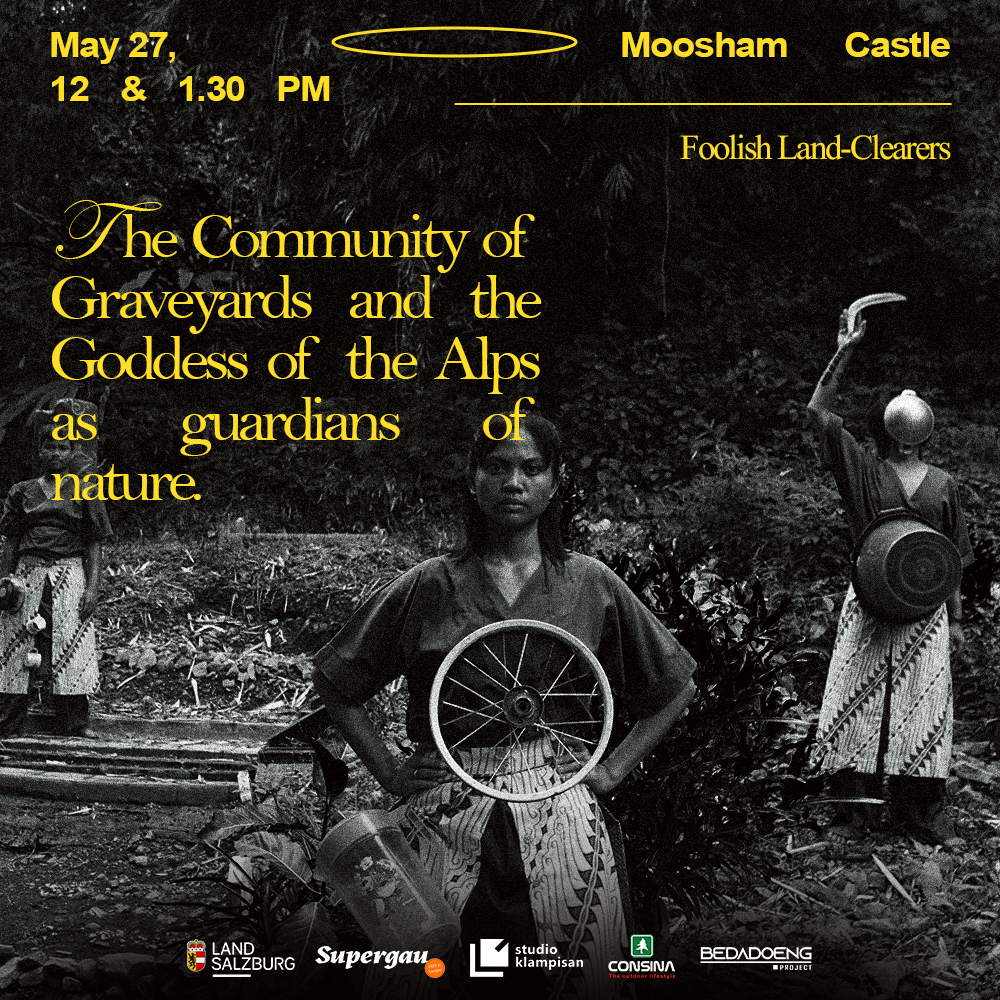

Author Abi Muhammad Latif

It is unknown why many land-clearing figures chose to be buried at the top of the hillocks, but the phenomenon of the community of graveyards has a great influence on the existence of the hillocks. Before discussing the guarding of the hillocks, I would like to describe a few possible references to the graveyard at the top of the hillocks.

The first reference comes from a spiritual perspective: the height is an effort to be close to the Creator. This is quite related to the stories of the spiritual journey of the prophets and the gods, where the redundant narrative is always talking about what is up high, going to the up high, the high throne, the 7th heaven. Statues that are used as a medium for praying are also positioned higher than the one praying. Perhaps by burying them at the top of the hillocks, they will be closer to the One Up High.

The second reference comes from identity politics and belonging. The title of “community leader” is attached to the land clearers, making their final resting place a special one. In terms of materiality, this makes it easier for people who miss, idolize, and want to pray for them to be able to know about and visit their graves.

They are acknowledged as people of importance, even spiritually, so that new rites are born which are carried out by the people for this community of graveyards. This further strengthens the identity politics of the land-clearers as the dominant entities that give birth to myths, energies, and imaginary spaces outside of themselves.

The main actors in the history of civilization often mark their areas of authority or track traces. If drawn to the concept of power, this practice of marking, materially, is a form of self-accomplishment of what they are trying to achieve. The community of graveyards immediately marked what the land-clearers had accomplished, and those that became theirs. This is also good in terms of ownership conflicts (in this case land) after they die: the hillock that has been divided among the descendants of the one buried on its top is difficult to be sold and dredged. Objections will arise on ethical grounds and fear of disaster. If the hillocks are dredged, then automatically the signs of “authentic” historical material will also disappear. Community of graveyards in the hillock area as the dominant entity, is quite strong and still relevant as one of the last strongholds to protect the existence of the hillocks from mining activities. Even though several hillocks that have burial complexes are also being dredged, the rites and pilgrimages to the graves of the land clearers are still going on. As collaborative work, there needs to be cultural regulations that also contribute to maintaining this community, so that the hillocks will keep their existence, and complexity – between the materialized and the imaginary.

Goddess Raetia, The Guardian of the Alpine Meadows

Sontga Margriata ei stada siat stads ad alp

Mai quendisch dis meins

In di eis ella ida dal stavel giu

Dada giu sin ina nauscha platta

Ch’igl ei scurclau siu bi sein alv

Paster petschen ha quei ad aguri cattau

«Quei sto nies signun ir a saver

Tgeinina zezna purschala nus havein»

The text above is the first stanza of Canzun de la Songta Margriata, an old Swiss folk song recorded by Caminada. The song tells of a woman named Margriata who was found in the Alm of the Alps – a summer meadow for the milking of cows, goats, and sheep, as well as cheese production. According to ancient rules, Alm is forbidden for women.

Margriata worked in the Alps for 7 summers, and to work there, she had to cover her chest. In her 7th year, Paster Petschen (the shepherd’s son) realized Margriata was a woman. Margriata offered 3 sheep that could be sheared 3 times a year to Paster Petschen, as a bribe so he would not report what he saw to Senn, the Chief Shepherd. Paster Petschen ignored Margriata’s offer and told the Head Shepherd. Senn has absolute authority over humans and animals, so Margriata must leave Alm. She left behind a dried spring, withered meadows, and weeping cows.

Santa Margaret (Margriata)—a name that may come from Raetia, Reita, or Risa. Her name bears a phonetic resemblance to Raetia. Like the Goddess Raetia in ancient times, Songta Margriata is the invisible protector of the Alpine meadows. She had her main temple at Este in the River Po valley.

Through phonetic changes, especially in the Swiss regions of Tessin and Grison, the name Goddess Raetia or Reisa changed to Risa, Madrisa/Matreia, or Mother Risa. Many place names throughout the Alps are composed with the names Reita, Risa or similar forms.

Eduard Renner, in his book “Golden Ring above Urion Raeto-Romanche folklore” (1991), cites an ancient Alpine hymn or blessing, which Senn had to sing every night for the protection of Alm, the shepherds and their livestock. Using a large milk funnel as a megaphone, he sings a long prayer in the meadow, ending each stanza with a refrain:

All around this meadow is a golden ring,

And there sits Maria with her dearest little child…

References:

https://pagaian.org/articles/mountain-goddess-of-the-alps-danu-raetia-marisa-by-claire-french-ph-d/

https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Canzun_de_Sontga_Margriata

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VPRLdcXU5eg

https://genius.com/Corin-curschellas-sontga-margriata-lyrics

The Community of Graveyards in the hillock area, in Sumbersari. Documentation: Studio Klampisan.

The Community of Graveyards on top of Bujuk Mareh hillock. Documentation: Studio Klampisan.

Bujuk Mareh graveyard on the top of hillock, Jenggawah. Documentation: Studio Klampisan.

The national hero’s grave on the excavated hillock. Documentation: Studio Klampisan.

Chapel in Tamsweg, Salzburg Lungau. Documentation: Studio Klampisan.

St Peter Cemetery in Salzburg. Documentation: Studio Klampisan.

St Peter Cemetery in Salzburg. Documentation: Studio Klampisan.