Author: Ahmad Siddiq Putra Yuda

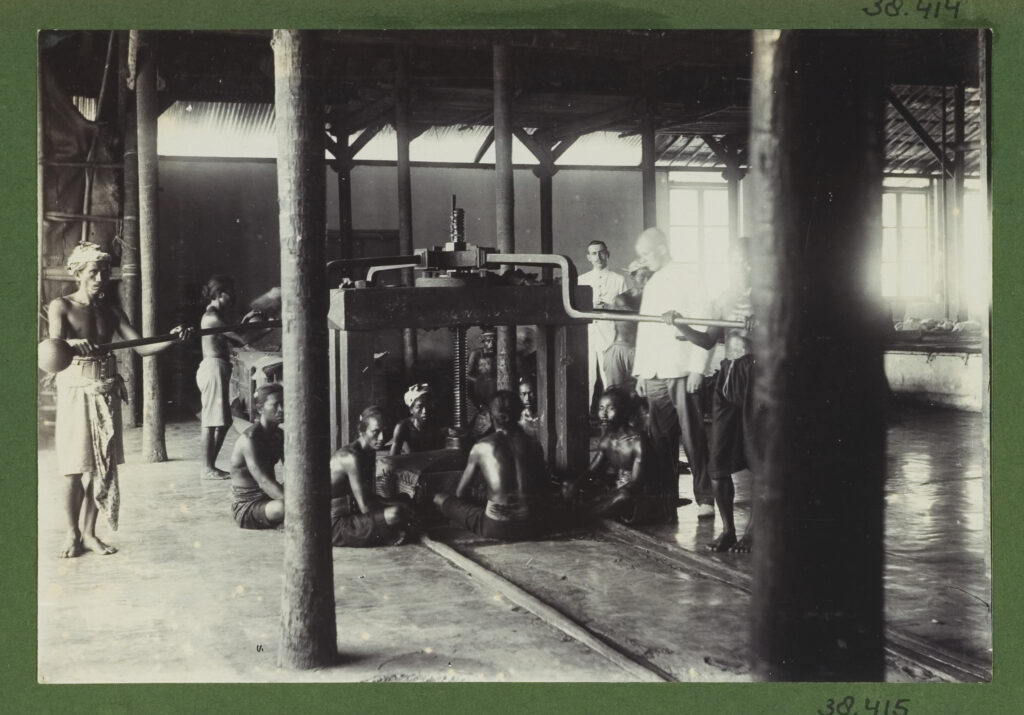

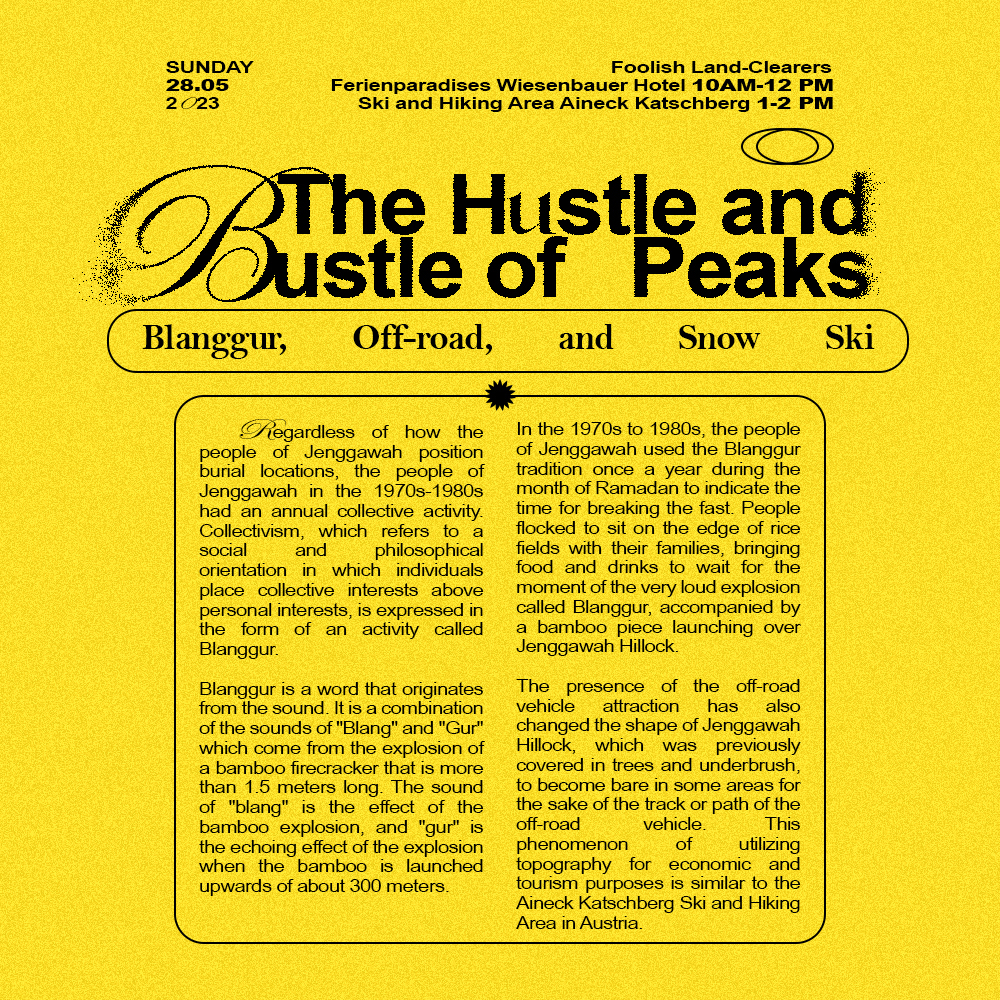

Exploitation is a familiar term in Jember when it comes to the existence of hillocks. Hillock is one of the icons or identities intentionally attached to Jember Regency, besides tobacco. “Jember—the City of 1000 Hillocks” then became a phrase often used to identify Jember. According to BAPPEDA Jember, in 2012, there were over 1670 hillocks in Jember which experienced a decrease of 11% to this day. The decrease was due to the exploitation or mining activities. The existence of hillocks, which is the result of sedimentation from the eruption of Mount Raung, makes the exploited hillocks unable to regrow.

Jember Regency has three types of varied hillocks, namely stone hillocks, plate stone hillocks and sand hillocks. These three variables are beneficial for the survival of all living organisms. First, the excessive amount and distribution of hillocks throughout Jember Regency serve as windbreakers, as the position of Jember Regency is surrounded by two large mountains: Mount Raung and Argopuro. Second, the macro climate. With the presence of hillocks, the temperature in the surrounding environment tends to be lower due to the many types of plants growing on hillocks and, as a result, this reduces the potential for drought. Third, biodiversity is preserved. However, this usefulness is apparently not the main priority of Jember Regency policymakers since hillocks are included in C mining.

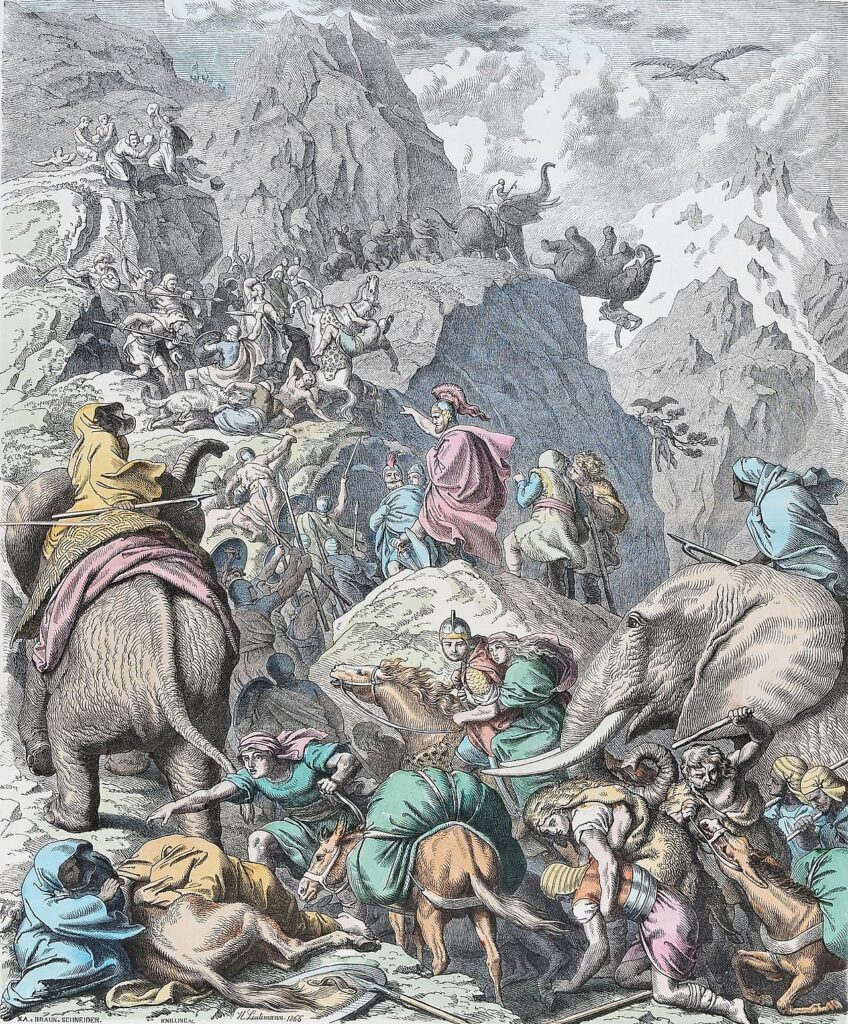

Mining practices on hillocks then shifted the function of hillocks, which essentially serve as an environmental balancer. This shift makes hillocks one of the commodities that has a high economic value because all materials contained in hillocks have economic value. Nature, which is the inorganic body of humans, must then be sacrificed to fulfill the needs (desires) of humans by sacrificing hillocks. In essence, humans must continue to dialogue with nature for their survival because humans are not able to live without nature. However, massive exploitation carried out on hillocks, where the stones are used for house foundations, decorations, and asphalt road mixtures, has the potential to bring negative impacts. For example, in research conducted by Puguh Akbar Priyanto in his thesis titled “Gumuk Exploitation in Antirogo Village,” it is explained that six whirlwind disasters occurred simultaneously in different places. The disasters occurred on March 29, 2013, in Kepatihan Village, Jember Lor, Kebonsari, Kaliwates District, and Patrang District.

The natural disaster phenomenon that occurs is not just because of God’s will or the anger of the hillocks’ stones that have become asphalt mixtures and house foundations. This happens because the former hillock mining lands have turned into residential and mini-market areas, so there are no longer natural windbreakers. For example, in Sumbersari District, a hillock that is well-known by the public as Kerang Hillock (literally translated as Clam Hillock) has now become a mall and apartment. The shifting of the function of hillocks, which were originally natural fortresses against wind and drought but now have turned into residential and mini-market areas, indicates that humans do not understand how nature works to fulfill basic human needs.

The Mount Raung and The Rest of Mount Gadung. Documentation: Google Earth.

Hillocks in Ledokombo, looking towards Mount Raung. Documentation: Google Earth.

Sepikul Hillock. Documentation: Rifandy P.

Kerang Hillock area has been transformed into residential areas, hotel, campus, and businesses. Documentation: Google Maps.