Dualism and Gendered Space in Javanese Architecture’s House

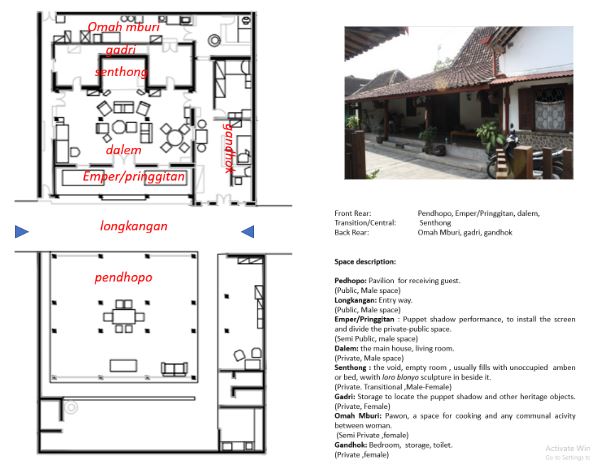

In Javanese vernacular architecture, the Javanese believe that the cosmos is composed of various opposing elements – heaven and earth, left and right, day and night, brightness and darkness, male and female, etc. Dualism denotes a state of two parts, of being dual; which refers to twofold divisions or a system of thought that recognizes two independent principles. The binary opposition between two elements is an important concept to understanding the cosmological principle. The Javanese believe that cosmos is formed by these dualisms, which was also the essential nature of Indochinese culture. These opposing binaries need to be placed, organized in a harmonious and balanced way, to gain cosmological equilibrium. In Javanese architecture, these cosmological dualisms express spatial metaphor and symbolism, to explain the structures of opposition within the Javanese’s built environment.

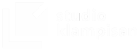

In that case, the Javanese people perceive their house as a microcosm of the natural universe, so they seek balance in their housing design (Frick, 1997; Tjahjono, 1989; Prijotomo, 1992; Himasari, 2011). This dualism concept became a foundation for viewing Javanese architecture from a philosophical perspective. In the practices, it contributes to how the physical order, forms, and activity of Javanese houses are constructed. The house became a dialectical interaction of opposites, in which balance is maintained through spatial division, representation, and functions. The traditional Javanese houses spatial division, consist of emper/pringgitan, ndalem, senthong, gadri mburi omah, and gandhok. Whereas in a noble house, having a high social position, there is one more room called pendopo (pavilion) (Budiana Setiawan, 2010). Every existing space is created to meet the needs of the homeowner.In Javanese vernacular architecture, the Javanese believe that the cosmos is composed of various opposing elements – heaven and earth, left and right, day and night, brightness and darkness, male and female, etc. Dualism denotes a state of two parts, of being dual; which refers to twofold divisions or a system of thought that recognizes two independent principles. The binary opposition between two elements is an important concept to understanding the cosmological principle. The Javanese believe that cosmos is formed by these dualisms, which was also the essential nature of Indochinese culture. These opposing binaries need to be placed, organized in a harmonious and balanced way, to gain cosmological equilibrium. In Javanese architecture, these cosmological dualisms express spatial metaphor and symbolism, to explain the structures of opposition within the Javanese’s built environment.

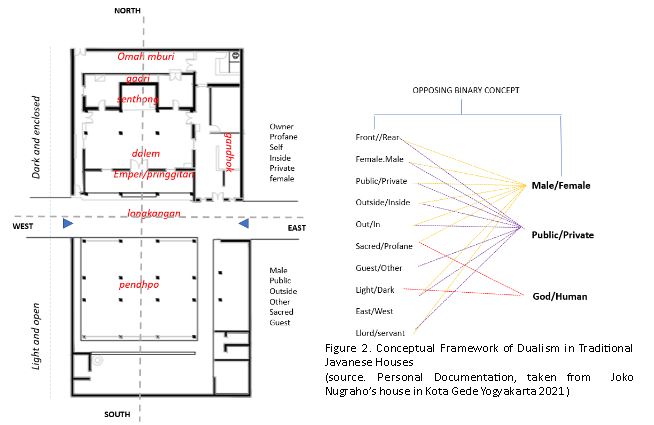

Another important concept in Javanese architecture is a hierarchy. The Javanese house was primarily arranged according to linear and centripetal organizations, which entailed the principles of duality and center (Prijotomos,1984). The Javanese house features spaces of opposite meanings, such as inner/outer, female/male, west/east but these opposites are neutralized and unified by a center. Moreover, the Javanese house is also divided into the front and rear, which respectively represent male and female domains, and at shadow plays/wayang represent the self and the other (Santosa , 2000). The boundary within the houses, formed as a line, wall, that divides the inner and outer space, and the pringgitan acts as the central point of the division of space. This transitional space metaphorically represents the transition from the universe to human space. It acts to clarify the meaning of duality and direction (Cairns, 1997; Mangunwijaya, 1992; Supriyadi, 2010).

For instance, the concept of duality is manifested in the north-south axis line which has a relationship between the spaces of Senthong, ndalem, peringgitan, pendopo, and emperan. The front room is open, bright, and has a low floor. On the contrary, the back room is closed, dark, and has a high floor. Based on the house axis line, the domination of certain rooms can be distinguished based on gender. The kitchen (pawon) is a place of dominance for women, while the hall is a place for male domination. Therefore, the ndalem and Senthong rooms are becoming ‘center’ used as harmonizing spaces that can be used by both men and women. In ndalem, there is also a subdivision of dominance based on gender. The west side of ndalem is used for women, while the eastern part is used for men. The middle part of ndalem is used as a harmonizing space that can be shared by both of them (Gunawan Tjahjono, 1990). As a result, the social and cultural roles of men and women were constructed especially in domestic space (Handayani and Sugiarti, 2001). In Javanese houses, gender context can be seen in the arrangement of rooms at home, in a form of domain’s separation of the area between sexes. This spatial separation is related to each gender’s roles and activities. In that case, the Javanese people perceive their house as a microcosm of the natural universe, so they seek balance in their housing design (Frick, 1997; Tjahjono, 1989; Prijotomo, 1992; Himasari, 2011). This dualism concept became a foundation for viewing Javanese architecture from a philosophical perspective. In the practices, it contributes to how the physical order, forms, and activity of Javanese houses are constructed. The house became a dialectical interaction of opposites, in which balance is maintained through spatial division, representation, and functions.

The traditional Javanese houses spatial division, consist of emper/pringgitan, ndalem, senthong, gadri mburi omah, and gandhok. Whereas in a noble house, having a high social position, there is one more room called pendopo (pavilion) (Budiana Setiawan, 2010). Every existing space is created to meet the needs of the homeowner. In Javanese vernacular architecture, the Javanese believe that the cosmos is composed of various opposing elements – heaven and earth, left and right, day and night, brightness and darkness, male and female, etc. Dualism denotes a state of two parts, of being dual; which refers to twofold divisions or a system of thought that recognizes two independent principles. The binary opposition between two elements is an important concept to understanding the cosmological principle. The Javanese believe that cosmos is formed by these dualisms, which was also the essential nature of Indochinese culture. These opposing binaries need to be placed, organized in a harmonious and balanced way, to gain cosmological equilibrium. In Javanese architecture, these cosmological dualisms express spatial metaphor and symbolism, to explain the structures of opposition within the Javanese’s built environment.

The house consists of the opposite element, such as public-private, male-female, and god-human. These dualisms are applied to how the spatial layout is constructed. The female space is the most secret and private of spaces, an enclosed space where outsiders are forbidden to enter. The male space, on the other hand, is where public practices take place, a bright and open area that outsiders are allowed to enter. As discussed above, a balance between the opposing elements can be achieved by the existence of a center. All Javanese houses feature a senthong tengah (in an ordinary house) or a krobongan (in a higher-status house). This centrality can be understood from the perspective of god/humans. Within the space, the idea of ‘centrality’ manifests as a link, harmonizer, or unifier between two opposing concepts. When these two concepts are combined, they will develop into the concept of natural reality which consists of three things, such as birth-life-death, creating-maintaining-fusing, the world above the world of the mankind-the underworld, and others. (Gunawan Tjahjono, 1990).

Pawon in Javanese House

The spatial arrangement in Javanese houses follows the idea of social space, in which the architecture is formed based on social products and activities conducted individually and socially. This idea is reflected in interior space, such as the types of furniture used to fill different functions according to the needs of its inhabitants, including furnishing inside pawon. The knowledge of spatial arrangement is passed through generation so that it becomes a pattern in the community. This pattern is internalized by individuals in the form of dispositions that become a reference in their actions. Whereas practice is an action taken by society in the context of social interaction based on habitus or what is called an objective structure (Bourdieu, 1997)

In that case, the spatial layout in Javanese houses is a manifestation of the Javanese social structure, which follows the patriarchal structure. In the house, the space is divided into male and female areas. Upon this practice, the house became a cultural artifact, in which the cultural value is reflected in daily spaces. On the household activity, one of the spatial cores in domestic space is pawon. Pawon, taken from the word ‘awu’ means ashes. Pawon uses as space for domestic production, the activity of cooking, preparing food, or consuming is occurred within these spaces. Moreover, Pawon is also a shared space, in which social activities such rewangan, are taken place. Rewangan is a social activity, when neighbors, relatives gather to cook and prepare food for rituals, family, or any cultural events. These traditions involve both women and men across generations, to gather and prepare for the food together. Pawon has become a ‘hub’ space, for stimulating cooperation, connecting the owner into a social sphere. In addition, Pawon is also used for family gatherings or receiving close guests, or even entertaining the guest in large amben. In the past, the women make a batik or woven bamboo in Pawon, in their spare time when they finish cooking. Although it perceives as dirty and located on the ‘back of the house, Pawon has duals meaning, a private activity such as cooking, storing family recipes, but at the same time a space that enables social collaborations/public. In this space, women play an important role to manage the workflow and gaining social networks. Pawon , perceived as a safe space for women, and has a strategic role in the life of Javanese’s daily activity.

The spatial arrangement in Javanese houses follows the idea of social space, in which the architecture is formed based on social products and activities conducted individually and socially. This idea is reflected in interior space, such as the types of furniture used to fill different functions according to the needs of its inhabitants, including furnishing inside pawon. The knowledge of spatial arrangement is passed through generation so that it becomes a pattern in the community. This pattern is internalized by individuals in the form of dispositions that become a reference in their actions. Whereas practice is an action taken by society in the context of social interaction based on habitus or what is called an objective structure (Bourdieu, 1997)

In that case, the spatial layout in Javanese houses is a manifestation of the Javanese social structure, which follows the patriarchal structure. In the house, the space is divided into male and female areas. Upon this practice, the house became a cultural artifact, in which the cultural value is reflected in daily spaces. On the household activity, one of the spatial cores in domestic space is pawon. Pawon, taken from the word ‘awu’ means ashes. Pawon uses as space for domestic production, the activity of cooking, preparing food, or consuming is occurred within these spaces. Moreover, Pawon is also a shared space, in which social activities such rewangan, are taken place. Rewangan is a social activity, when neighbors, relatives gather to cook and prepare food for rituals, family, or any cultural events. These traditions involve both women and men across generations, to gather and prepare for the food together. Pawon has become a ‘hub’ space, for stimulating cooperation, connecting the owner into a social sphere. In addition, Pawon is also used for family gatherings or receiving close guests, or even entertaining the guest in large amben. In the past, the women make a batik or woven bamboo in Pawon, in their spare time when they finish cooking. Although it perceives as dirty and located on the ‘back of the house, Pawon has duals meaning, a private activity such as cooking, storing family recipes, but at the same time a space that enables social collaborations/public. In this space, women play an important role to manage the workflow and gaining social networks. Pawon , perceived as a safe space for women, and has a strategic role in the life of Javanese’s daily activity.

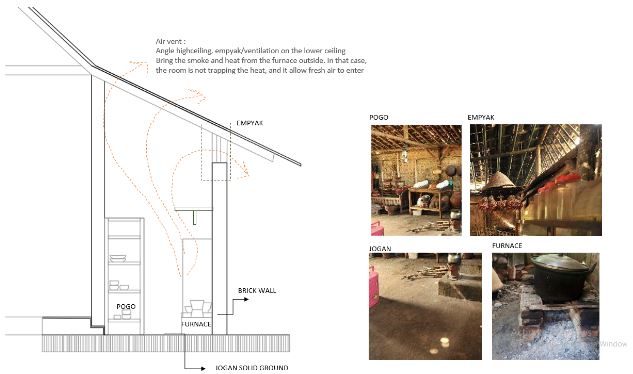

One most important feature in pawon architecture are the furnace. As pawon has become a woman territory, the women have the opportunity to develop furnaces with various models and with various materials of fuels that exist in the environment as long as all with ecological considerations. The pawon architecture, tightly related to how the furnace is placed and circulates the smoke into outer space. Pawon is enclosed with many ventilations on the edge between the wall and roof’s beam. Then is also supported by the openings that invite the airflow and cross ventilation to minimize the room heat. Pawon, utilized semi-open space with no rigid boundaries in the interior. The idea of interior space is defined by the arrangement of the cooking utensils. This spatiality supported the flexibility of the space, in which the space can be turned into a shared or private space. It did not follow the rigid functionality that the modern kitchen offers. Most of the pawon’s space has a high ceiling, to capture the heat and blow the air through the ventilation and roof tile’s gap. The high ceiling is also used to dry out the harvest, as the furnace’s smoke goes up to the ceiling. While the wall details on the pawon/kitchen are all made of masonry or woven bamboo equipped with double layers door. with the All walls somehow look black /dirty because of the soot coming from the burning furnace. The floor, made from solid ground, with no tiles. Pawon, also usually has a side door and back door access. Since the function of this space is to utilize more intimate interactions between neighbors and relatives, they usually enter through the back/side door. These doors, used by the servant or any activity that requires heavy loadings. The back/side door, connect to the backyard, which becomes a hub or communal space for several houses. These layers of space signified how both individual and social interactions, construct by spatial logic. The pawon, even though it became an ‘enclose’ space, dark, humid like a womb, also can become an open space, space for social interactions between intimate relatives.

Technically speaking, with the spatial functionality, pawon produce heat and smoke that undermine the other house structure. This is the reason why, pawon is usually placed in omah mburi, detach from the main masses. The detachment allows one standing room, that has more flexibility to access the open air. So, the air thermal within the main houses cannot be influenced by the heat produced, and smoke from pawon. Another dualism perspective, in which pawon became a safe space for women, but also the most dangerous space from a technical point of view. Then when the element of fire meets water, the cooking activity always involved these two sources. The woman who is in charge of pawon, plays an important role in balanced-out this opposite element, to breathe life into the households.

Dea Widya

Dea Widya (b. 1987, Blora) is an artist based in Bandung, Indonesia. Dea Widya is an Architecture graduate from the Bandung Institute of Technology, and often adopts design approaches in her experiments on the relationship between art and architecture, which exposes the invisible sides of architecture. She decided to take a postgraduate course in Fine Arts and explore the concept of space into installations, after working for an architectural design consulting firm and struggling to find the artistic/aesthetic side of architectural design. She explores a lot of site-specific and mixed media works, which are related to issues of city, space and architecture. Her method of work is related to cross-disciplinary research and collaboration.

Some of her works have been exhibited at the Power and Other Things exhibition, Europalia 2017, Jakarta Biennale 2015, Artjog 2015, 2019, Southeast Asia Triennale 2016, and London Design Biennale 2021. Besides that, she also teaches interior design at a private university, and conducts research that focuses on aspects of narrative, recollection, and memory in space.